By Michael Pickering

This name encompasses the category of chemicals that living organisms make which are not used in their normal growth, development, or reproduction. They are a staggering array of chemical structures and properties. Antibiotics are largely produced by bacteria, and a large variety of mammalian toxins are of fungal origin. Pigments are produced by both botanicals and insects. The peyote cactus, Lophophora williamsii, produces the hallucinogenic alkaloid mescaline. Fugu, the Chinese puffer fish, harbor symbiotically produced tetrodotoxin.

Lotus scoparius, or deer weed, makes a water-soluble flavinoid, which is a biodegradable germination inhibitor, and stores in its seeds. Upon first rain, this compound sterilizes the surrounding ground so that no seeds can germinate. The result is that competitive weed seeds rot. When the second rain comes, the deer weed seeds germinate with nothing but clear sky surrounding them.

Sometimes, we can see a competitive advantage of the presence of these chemicals: attracting pollinators, protective insects, or mates, or discouraging predators, competitors, or tramplers. But often not. Today’s musings are about two species (an insect and a botanical): Daclylopius coccus and Citrus sinensis.

"Gusano Rojo", Dactylopius coccus

Red dyes produced by insects have been and remain among the most important dyestuffs in human commerce. Before the Americas were exploited, the most abundant source of red pigments was the Asian scale insects and their excretions. This broad class of quinoid dyes bind permanently to proteinaceous substrates (in dye talk they are ‘fast’) such as wool and silk. Historically, they have also been used as art pigments.

Early in the 16th century, the Spanish introduced the world to the American cochineal, and the Asian scale insects were doomed to a mere historical reference.

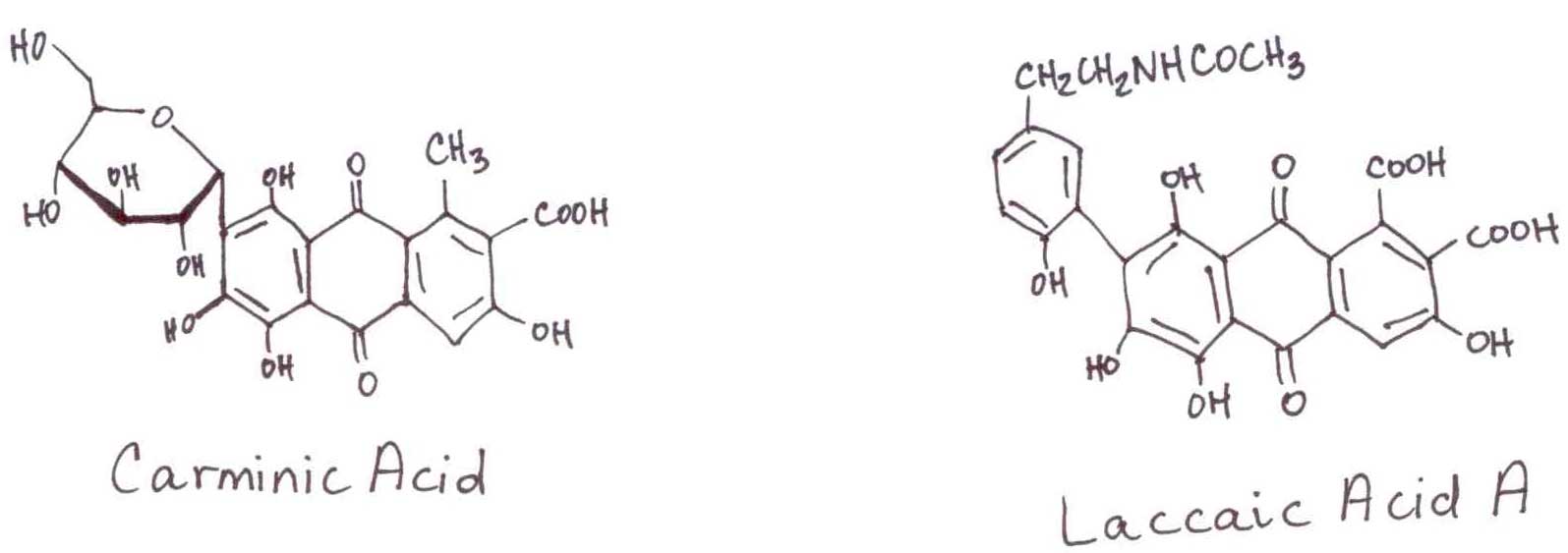

The females of this American species that feeds on cactus provide the popular Latino name “red worm.” Interestingly, Dactylopius coccus is not actually a worm, but is part of the cochineal family. By dry weight, the females can produce an astounding double digit percentage of pigment. The pigments have great variation of color and intensity (Carminic Acid extinction coefficient 6800, Laccaic Acid A extinction coefficient 43700). The commercial growers of the pigment use the cactus Indian Fig Opuntia (Opuntia ficus-indica) to feed the caterpillars, whose fruit and tender young shoots are also popular in Latino diets. The same insects in a blue agave farm are considered a pest.

Because of the significance of these insect-derived pigments in human history, they are the subject of anthropological study in ancient art. In 2004, we were invited into the study by the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research of the Smithsonian Institute. Although the pigments have long wavelength chromophores (little or no interference) and large extinction coefficients, the sample size is only 2-5 ng to minimize damage. As the pigments are only a small component of the sample, adequate detection requires a post-column reaction to make the pigments fluorescent. We made them an inert system as the reagent AlCl3 is a powerful reducing agent, which translates as very corrosive to hardware. During the reaction, the Al3+ reduces the quinone to a hydroquinone, which chelates the spent Al3+ and makes the entire complex fluorescent.

Oranges, Citrus sinensis

Valencia oranges produces two main bitter principles, Limonin, a terpenoid, and Naringin, a flavenoid, which it mainly stores in its seeds. The seeds are easily removed when the fruit is harvested for juice. Lacking seeds, the navel orange must develop a different storage strategy.

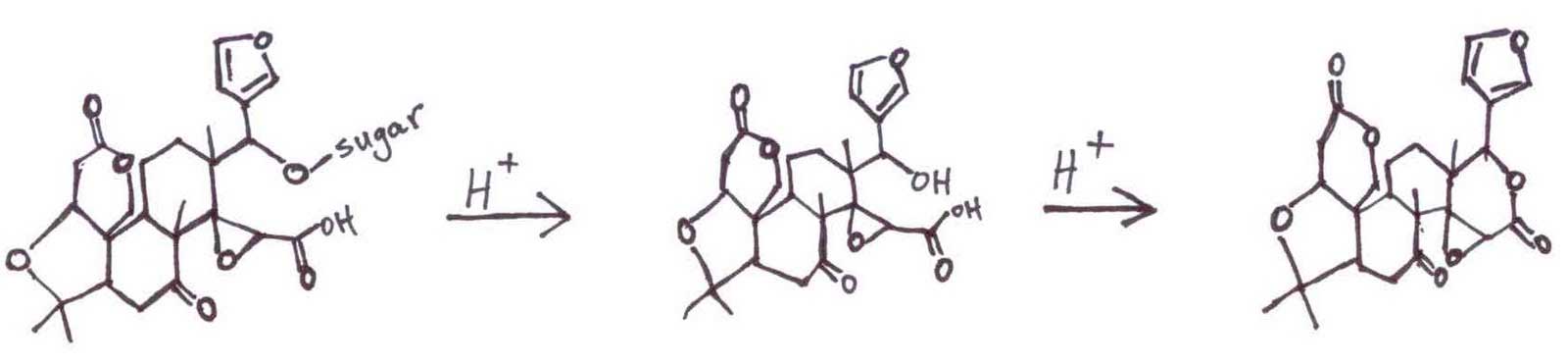

The navel orange stores the Limonin and Naringin as tasteless precursors (at neutral pH) in the peel, concentrated in the vestigial seed, the navel end. When the orange is juiced, the membranes are torn and spill their contents into the acidic juice. The acidity catalyzes the hydrolytic elimination of a sugar from a tertiary alcohol and facilitates a ring-closure to form a lactone, the bitter Limonin.

The tasteless Naringin precursor reacts similarly.

California, and I am sure other commercial orange-producing areas, has strict standards for exportability of the whole fruit, size being paramount. Thus, the most important commercial value in un-exportable fruit is the juice. One hundred percent navel orange juice is unpalatably bitter.

It is my opinion, and I encourage you to compare, that non-specific blended frozen orange juice concentrates contain a noticeable amount of navel orange juice. Pure Valencia concentrate is available, so do the experiment and voice your opinion. We will post opinions (with your bylines, or make up a cool avatar name) in the next newsletter.

Further Reading and Photo Credits:

http://www.teotitlan.com/naturaldyes.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_dye

1) Peyote photo from Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Peyote_Cactus.jpg#file

2) Puffer fish Photo by Mikael:

http://www.gastroville.com/2009/12/06/tidbits-from-japan/

3) Cochineal Photos from Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cochineal